Diagnosis and Associated Comorbidities

Associated Comorbidities and Clinician Roles in Diagnosis

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a complication of diabetes that causes damage to the blood vessels of the retina; it is the most common cause of irreversible blindness in working-age Americans.1

It is possible to have DR in one or both eyes for a long time without noticing symptoms until substantial damage has occurred. Symptoms may include:1

- Blurred or double vision

- Difficulty reading

- The appearance of spots — commonly called “floaters” — in your vision

- A shadow across the field of vision

- Eye pain or pressure

- Difficulty with color perception

- Disease duration: the longer someone has diabetes, the greater the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy

- Poor control of blood sugar levels over time

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol levels

- Pregnancy

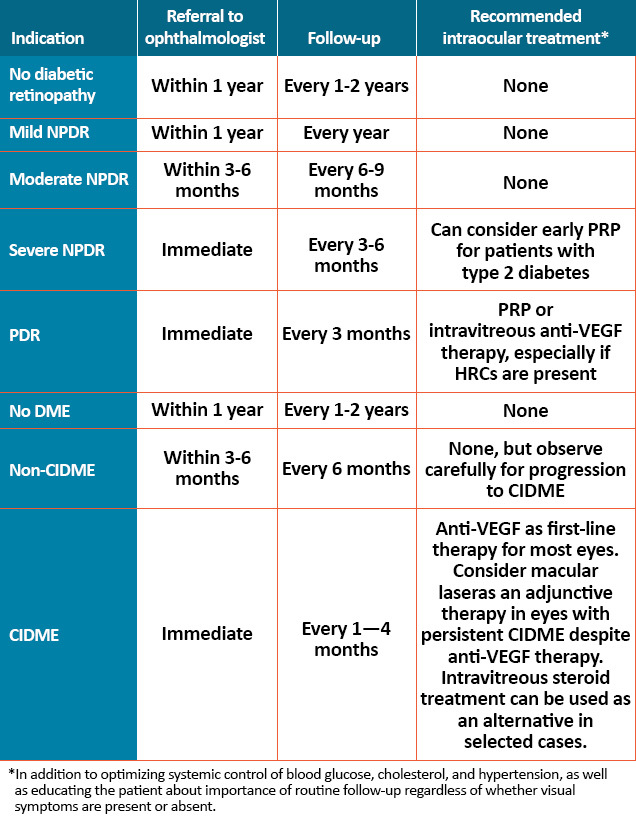

In patients with diabetes, a comprehensive eye exam should be performed at least initially and at intervals thereafter as recommended by an eye care professional and as noted in the following Table. Results of eye examinations should be documented and transmitted to the referring healthcare professional.2

CIDME = central involved diabetic macular edema; DME = diabetic macular edema; HRCs = high-risk characteristics;

NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PRP = panretinal photocoagulation;

VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor.

An ophthalmologist or optometrist who is knowledgeable and experienced in diagnosing Diabetic Retinopathy should perform the examinations.2 The goal of optometrists, as the primary eye care providers for a majority of Americans with, and at risk for, diabetes, is to prevent patients with diabetic eye disease from progressing to the level of sight-threatening retinopathy. If DR is present, prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is recommended.3

Surveys have shown that patients fear vision loss as much as or more than any other disability. Optometrists are often an entry point for patients who otherwise may not receive routine health care and influence patient attitudes and behaviors by explicitly linking prevention of vision loss to prevention or worsening of diabetes through healthy lifestyle choices. Optometrists assist in the early identification of diabetes by evaluating for ophthalmic signs and symptoms like refractive fluctuation, ocular surface disease, recurrent staphylococcal lid disease, dermatologic changes like acanthosis nigricans, and unexplained retinopathy, and by using simple, validated in-office screening tools for undiagnosed diabetes.3

To detect sight-threatening retinopathy, optometrists must start with a thorough clinical examination through dilated pupils. The index of suspicion should be elevated when patients have a higher risk profile (high hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c], long diabetes duration, type 1 diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, untreated sleep apnea, clinical depression, and presence of other diabetes complications).3 Early diagnosis of NPDR provides the opportunity for optometrists to collaborate with both patients and their other doctors to mitigate the risk for further progression.

Comprehensive evaluation by an ophthalmologist will include dilated slit-lamp examination including biomicroscopy with a hand-held lens, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and testing as appropriate that may include optical computed tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography. Retinal photography, with remote reading by experts, has great potential to provide screening services in areas where qualified eye care professionals are not readily available.2 High-quality fundus photographs can detect most clinically significant diabetic retinopathy. Interpretation of the images should be performed by a trained eye care provider. In-person exams are still necessary when the retinal photos are unacceptable and for follow-up if abnormalities are detected.

Improved detection is important; an estimated 30% of patients with NPDR have retinal abnormalities primarily outside the posterior pole, a finding that underscores the importance of examining the mid-peripheral and peripheral retina for retinopathy in every patient with known or suspected diabetes and the additional value of ultra-widefield imaging.3 An analysis also found that patients with NPDR lesions predominantly in the periphery (outside the standard Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study [ETDRS] fields) were 3.2 times more likely to have a two-step worsening and 4.7 times more likely to progress to PDR in the course of four years.3

References

- American Society of Retina Specialists (ASRS). Diabetic retinopathy. https://www.asrs.org/patients/retinal-diseases/3/diabetic-retinopathy. Accessed November 26, 2019.

- Solomon SD, Chew E, Duh EJ, et al [2017 ADA Position Statement]. Diabetic retinopathy: A position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(3):412–418.

- Chous AP. Take charge of diabetic care. https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/take-charge-of-diabetic-care.

Accessed November 26, 2019.